Until All the Story is Written

I will believe You for my future, chapter by chapter, until all the story is written. (from Brendan Liturgy, Part XVI in Celtic Daily Prayer)

How many stories have you written for your life? I have had multiple versions. As an elementary school student I wanted to be a ballerina; as a high school student, a CEO; and as a soon to be college graduate, a professor. None of these became a reality. I’ve also done this with relationships—imagining a narrative that will go on to the end of my life—whether with my parents or a possible significant other. By creating these stories, I think I have some level of control. With any potential problems solved in my head, I can then set up the path and relax.

But not for long. I have yet to have any of those stories come to fruition. Furthermore, at times I can become so wedded to one of the stories, almost as if my honor is connected to them, that I try to make them work out even though a deep part of me is crying—stop. A more serious problem occurs when I create roles for other people apart from recognizing their individual agency. When they don’t follow my script I allow relationships to break down and I miss the rich interactions that are actually happening in front of me.

Clearly, the future doesn’t happen because I picture and plan it. If I look back, some of the most meaningful chapters in my life have come because I was ready to step out and say yes to something unexpected. Such as a golf outing that circuitously led to my working at the Cincinnati Zoo or saying yes to a conversation at a camp thirty years ago. Neither of these things happened because of my writing the story.

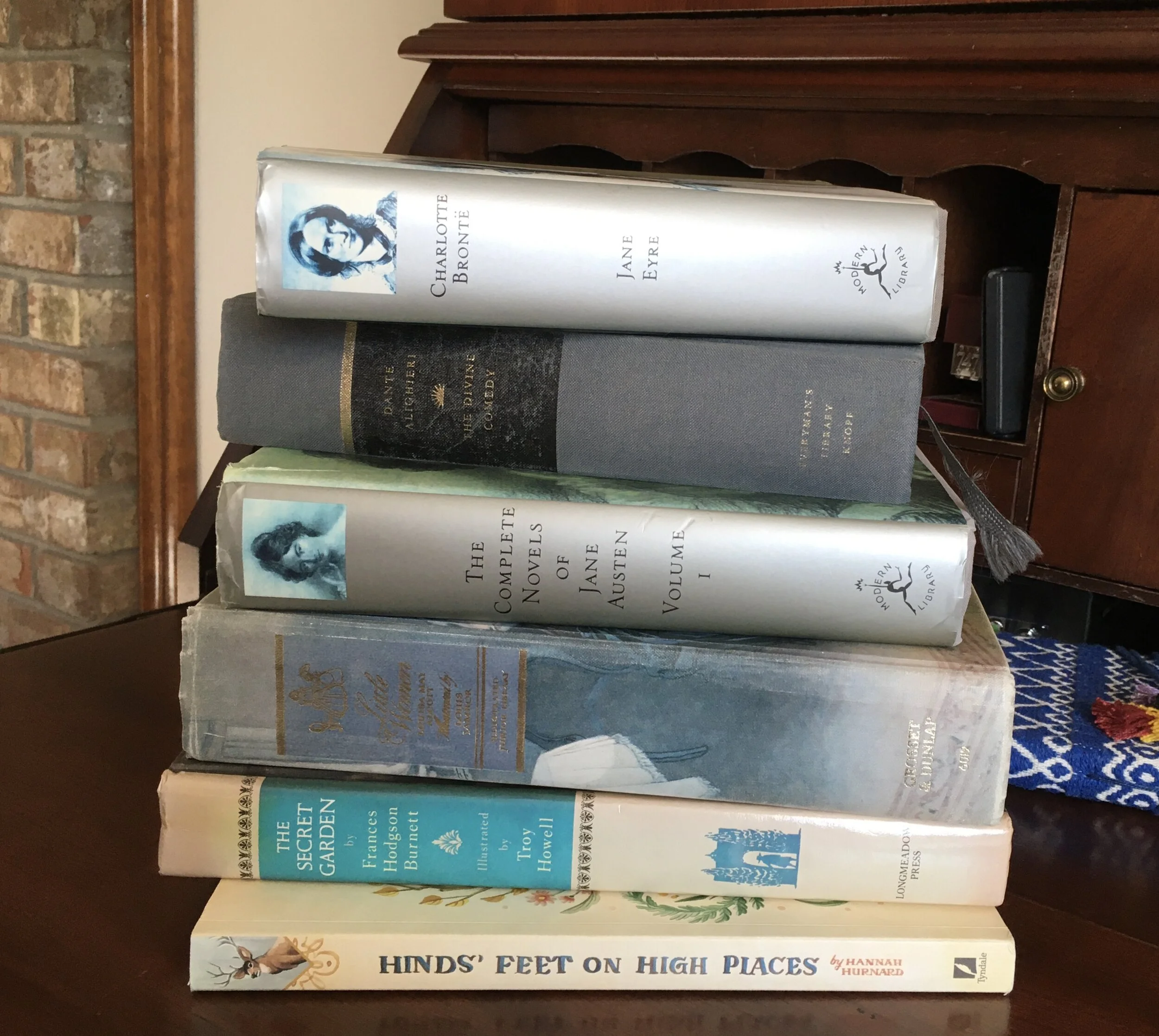

Contrary to the imagined order that a well-planned story lulls me into believing, growth occurs in the tensions and conflicts of life. A story builds as the various characters interact with one another and their setting. The outcomes are never certain. As a reader, I may be comfortable with novels as I see the overall trajectory of the story. But I’m not merely the reader of my life, I’m the protagonist. Within a novel the characters don’t know what will happen. That’s where we find ourselves. We are not the authors, but we know the One who is.

In the book of Ruth in the Hebrew scriptures, we encounter several characters whose life stories are different from what they would have written. It begins by introducing three widows who would have dreamt of living a long life with their husbands—Naomi, Orpah, and Ruth. Then a landowner, Boaz, who probably had thoughts of sustaining the property he already owned. But neither Ruth nor Boaz hang onto their original stories. When life changes, they engage with the circumstances before them. She travels to Bethlehem with Naomi and marries again. He embraces his role as a kinsman redeemer to marry Ruth, a foreigner, and redeem Naomi’s husband’s land. Both take faithful actions as they interact within the circumstances and people around them. Through this faithfulness they become the ancestors of King David and eventually Jesus.

A new sense of freedom comes with such a way of living. Without trying to arrive at a specific future, and by trusting God to develop the full story, I can be expectant for God’s work and direction in my life instead of worried about my machinations. I still have room to dream and to chart some paths based on those dreams. But then I can open my hands to allow God to write the chapters and even let go of my dreams for something more magnificent. I can invite him into the uncertainty and not try to mold an outcome. Now that is a story I would want to read.